Bestiary

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

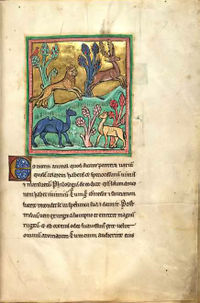

"The

Leopard" from the 13th-century bestiary entitled "Rochester

Bestiary."

A pelican

vulning (i.e., wounding) itself

A bestiary, or Bestiarum

vocabulum is a compendium of beasts. Bestiaries were made popular in the Middle

Ages in illustrated volumes that described various animals, birds and even

rocks. The natural history and illustration of each beast was usually

accompanied by a moral lesson. This reflected the belief that the world itself

was literally the Word of God, and that every living thing had its own special

meaning. For example, the pelican, which was believed to tear open its breast

to bring its young to life with its own blood, was a living representation of Jesus.

The bestiary, then, is also a reference to the symbolic language of animals in

Western Christian art and literature.

Bestiaries were

particularly popular in England and France around the 12th century and were

mainly compilations of earlier texts. The earliest bestiary in the form in

which it was later popularized was an anonymous 2nd century Greek volume called

the Physiologus, which itself summarized ancient knowledge and wisdom

about animals in the writings of classical authors such as Aristotle's Historia

Animalium and various works by Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, Solinus, Aelian

and other naturalists.

Following the Physiologus,

Saint Isidore of Seville (Book XII of the Etymologiae) and Saint Ambrose

expanded the religious message with reference to passages from the Bible and

the Septuagint. They and other authors freely expanded or modified pre-existing

models, constantly refining the moral content without interest or access to

much more detail regarding the factual content. Nevertheless, the often

fanciful accounts of these beasts were widely read and generally believed to be

true. A few observations found in bestiaries, such as the migration of birds,

were discounted by the natural philosophers of later centuries, only to be

rediscovered in the modern scientific era.

The Italian artist Leonardo

da Vinci also made his own bestiary.

The most well-known

bestiary of that time is the Aberdeen Bestiary. There are many others and over

50 manuscripts survive today.

In modern times, artists

such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Saul Steinberg have produced their own

bestiaries. Jorge Luis Borges wrote a contemporary bestiary of sorts, the Book

of Imaginary Beings, which collects imaginary beasts from bestiaries and

fiction. Writers of Fantasy fiction draw heavily from the fanciful beasts

described in mythology, fairy tales, and bestiaries. The "worlds"

created in Fantasy fiction can be said to have their own bestiaries. Similarly,

authors of fantasy role-playing games sometimes compile bestiaries as

references, such as the Monster Manual for Dungeons & Dragons.

It is not uncommon for video games with a large variety of enemies (especially RPGs)

to include a bestiary of sorts. This usually takes the form of a list of

enemies and a short description (e.g. the Metroid Prime and Castlevania games,

as well as Dark Cloud and Final Fantasy).

Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Bestiary&action=history

"The

Leopard" from the 13th-century bestiary entitled "Rochester

Bestiary."

A pelican

vulning (i.e., wounding) itself

A bestiary, or Bestiarum

vocabulum is a compendium of beasts. Bestiaries were made popular in the Middle

Ages in illustrated volumes that described various animals, birds and even

rocks. The natural history and illustration of each beast was usually

accompanied by a moral lesson. This reflected the belief that the world itself

was literally the Word of God, and that every living thing had its own special

meaning. For example, the pelican, which was believed to tear open its breast

to bring its young to life with its own blood, was a living representation of Jesus.

The bestiary, then, is also a reference to the symbolic language of animals in

Western Christian art and literature.

Bestiaries were

particularly popular in England and France around the 12th century and were

mainly compilations of earlier texts. The earliest bestiary in the form in

which it was later popularized was an anonymous 2nd century Greek volume called

the Physiologus, which itself summarized ancient knowledge and wisdom

about animals in the writings of classical authors such as Aristotle's Historia

Animalium and various works by Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, Solinus, Aelian

and other naturalists.

Following the Physiologus,

Saint Isidore of Seville (Book XII of the Etymologiae) and Saint Ambrose

expanded the religious message with reference to passages from the Bible and

the Septuagint. They and other authors freely expanded or modified pre-existing

models, constantly refining the moral content without interest or access to

much more detail regarding the factual content. Nevertheless, the often

fanciful accounts of these beasts were widely read and generally believed to be

true. A few observations found in bestiaries, such as the migration of birds,

were discounted by the natural philosophers of later centuries, only to be

rediscovered in the modern scientific era.

The Italian artist Leonardo

da Vinci also made his own bestiary.

The most well-known

bestiary of that time is the Aberdeen Bestiary. There are many others and over

50 manuscripts survive today.

In modern times, artists

such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Saul Steinberg have produced their own

bestiaries. Jorge Luis Borges wrote a contemporary bestiary of sorts, the Book

of Imaginary Beings, which collects imaginary beasts from bestiaries and

fiction. Writers of Fantasy fiction draw heavily from the fanciful beasts

described in mythology, fairy tales, and bestiaries. The "worlds"

created in Fantasy fiction can be said to have their own bestiaries. Similarly,

authors of fantasy role-playing games sometimes compile bestiaries as

references, such as the Monster Manual for Dungeons & Dragons.

It is not uncommon for video games with a large variety of enemies (especially RPGs)

to include a bestiary of sorts. This usually takes the form of a list of

enemies and a short description (e.g. the Metroid Prime and Castlevania games,

as well as Dark Cloud and Final Fantasy).