http://www.photonette.net/

http://www.photonette.net/

Horse

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Domestic Horse

Conservation status

Domesticated

Scientific classification

Kingdom:

Animalia

Phylum:

Chordata

Class:

Mammalia

Order:

Perissodactyla

Family:

Equidae

Genus:

Equus

Species:

E.

caballus

Binomial name

Equus

caballus

Linnaeus, 1758

The horse (Equus

caballus, sometimes seen as a subspecies of the Wild Horse, Equus ferus

caballus) is a large odd-toed ungulate mammal, one of ten modern species of

the genus Equus. Horses have long been among the most economically

important domesticated animals; although their importance has declined with

mechanization, they are still found worldwide, fitting into human lives in

various ways. The horse is prominent in religion, mythology, and art; it has

played an important role in transportation, agriculture, and war; it has

additionally served as a source of food, fuel, and clothing.

Almost all breeds of horses

can, at least in theory, carry humans on their backs or be harnessed to pull

objects such as carts or plows. However, horse breeds were developed to allow

horses to be specialized for certain task; lighter horses for racing or riding,

heavier horses for farming and other tasks requiring pulling power. In some

societies, horses are a source of food, both meat and milk; in others it is taboo

to consume them. In industrialized countries horses are predominantly kept for

leisure and sporting pursuits, while they are still used as working animals in

many other parts of the world.

Biology

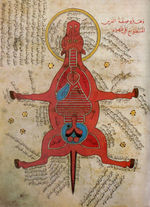

Anatomy of

a horse from an Egyptian document (15th century)

Age

Depending on breed,

management and environment, the domestic horse today has a life expectancy of

25 to 30 years. Some specific breeds of horse can live into their 40s, and,

occasionally, beyond. The oldest verifiable record was "Old Billy," a

horse that lived in the 19th century to the age of 62.[1]

Size

The size of horses varies

by breed, but can also be influenced by nutrition. The general rule for cutoff

in height between what is considered a horse and a pony at maturity is 14.2 hands(h

or hh) (147 cm, 58 inches) as measured at the withers. An animal 14.2h or over

is usually considered a horse and one less than 14.2h is a pony.

However, there are

exceptions to the general rule. Some smaller horse breeds who typically produce

individual horses both under and over 14.2h are considered "horses"

regardless of height. Likewise, some pony breeds, such as the Pony of the

Americas or the Welsh cob, share some features of horses and individual animals

may occasionally mature at over 14.2h, but are still considered ponies.

The difference between a

horse and pony is not simply a height difference, but also a difference in phenotype

or appearance. There are noticeable differences in conformation and

temperament. Ponies often exhibit thicker manes, tails and overall coat. They

also have proportionally shorter legs, wider barrels, heavy bone, thick necks,

and short heads with broad foreheads.

Light horses such as Arabians,

Morgans, Quarter Horses, Paints and Thoroughbreds usually range in height from

14.0 to 16.0 hands and can weigh from 850 lbs to about 1500 lbs. Heavy or draft

horses such as the Clydesdale, Belgian, Percheron, and Shire are usually at

least 16.0 to 18.0 hands high and can weigh from about 682 kg (1500 lb) up to

about 900 kg (2000 lb). Ponies are less than 14.2h, but can be much smaller,

down to the Shetland pony at around 10 hands, and the Falabella which can be

the size of a medium-sized dog. The miniature horse is as small as or smaller

than either of the aforementioned ponies but are classified as very small horses

rather than ponies despite their size.

The largest horse in

history was a Shire horse named Sampson, later renamed Mammoth, foaled in 1846

in Bedfordshire, England. He stood stood 21.2˝ hands high (i.e. 7 ft 2˝ in or

2.20 m ), and his peak weight was estimated at over 3,300 lb (approx 1.5

tonnes). The current record holder for the world's smallest horse is Thumbelina,

a fully mature miniature horse affected by dwarfism. She is 17 inches tall and

weighs 60 pounds.[2]

Reproduction

and development

Pregnancy lasts for

approximately 335-340 days and usually results in one foal (male: colt, female:

filly). Twins are rare. Colts are usually carried 2-7 days longer than fillies.

Females 4 years and over are called mares and males are stallions. A castrated

male is a gelding. Horses, particularly colts, may sometimes be physically

capable of reproduction at approximately 18 months but in practice are rarely

allowed to breed until a minimum age of 3 years, especially females. Horses

four years old are considered mature, though the skeleton usually finishes

developing at the age of six, and the precise time of completion of development

also depends on the horse's size (therefore a connection to breed exists),

gender, and the quality of care provided by its owner. Also, if the horse is

larger, its bones are larger; therefore, not only do the bones take longer to

actually form bone tissue (bones are made of cartilage in earlier stages of

bone formation), but the epiphyseal plates (plates that fuse a bone into one

piece by connecting the bone shaft to the bone ends) are also larger and take

longer to convert from cartilage to bone as well. These plates convert after

the other parts of the bones do but are crucial to development.

Depending on maturity,

breed and the tasks expected, young horses are usually put under saddle and trained

to be ridden between the ages of two and four. Although Thoroughbred and American

Quarter Horse race horses are put on the track at as young as two years old in

some countries (notably the United States), horses specifically bred for sports

such as show jumping and dressage are generally not entered into top-level

competition until a minimum age of four years old, because their bones and

muscles are not solidly developed, nor is their advanced training complete.

Teeth

Horses are adapted to grazing,

so their teeth continue to grow throughout life. There are 12 teeth (six upper

and six lower), the incisors, adapted to biting off the grass or other

vegetation, at the front of the mouth, and 24 teeth, the premolar and molars,

adapted for chewing, at the back of the mouth. Stallions and geldings have four

additional teeth just behind the incisors, a type of canine teeth that are

called "tushes." Some horses, both male and female, will also develop

one to four very small vestigial teeth in front of the molars, known as

"wolf" teeth, which are generally removed because they can interfere

with the bit.

There is an empty

interdental space between the incisors and the molars where the bit rests

directly on the bars (gums) of the horse's mouth when the horse is bridled.

The incisors show a

distinct wear and growth pattern as the horse ages, as well as change in the

angle at which the chewing surfaces meet, and while the diet and veterinary

care of the horse can affect the rate of tooth wear, a very rough estimate of

the age of a horse can be made by looking at its teeth.

General

anatomy

Horses have, on average, a skeleton

of 205 bones. A significant difference in the bones contained in the horse

skeleton, as compared to that of a human, is the lack of a collarbone--their front

limb system is attached to the spinal column by a powerful set of muscles,

tendons and ligaments that attach the shoulder blade to the torso. The horse's

legs and hooves are also unique, interesting structures. Their leg bones are

proportioned differently from those of a human. For example, the body part that

is called a horse's "knee" is actually the carpal bones that

correspond to the human wrist. Similarly, the hock, contains the bones

equivalent to those in the human ankle and heel. The lower leg bones of a horse

correspond to the bones of the human hand or foot, and the fetlock (incorrectly

called the "ankle") is actually the proximal sesamoid bones between

the cannon bones (a single equivalent to the human metacarpal or metatarsal

bones) and the Proximal phalanges, located where one finds the

"knuckles" of a human. A horse also has no muscles in its legs below

the knees and hocks, only skin and hair, bone, tendons, ligaments, cartilage,

and the assorted specialized tissues that make up the hoof (see section hooves,

below).

A horse's digestive system

is adapted to a forage diet of grasses and other plant material, consumed

regularly throughout the day, and so they have a relatively small stomach but

very long intestines to facilite a steady flow of nutrients. Horses are not ruminants,

so they have only one stomach, like humans, but unlike humans, they can also

digest cellulose from grasses due to the presence of a cecum, or "water

gut" that is part of their large intestine. Unlike humans, horses cannot vomit,

so digestion problems can quickly spell trouble, with colic a leading cause of

death.

As prey animals, they have

very large eyes (only the whale has a larger eye), with excellent day and night

vision, though they may have a limited range of color vision. While not color-blind,

studies indicate that they have difficulty distinguishing greens, browns and

grays. Their hearing is good, and their ears can rotate to pick up sound from

any direction. Their sense of smell, while much better than that of humans, is

not their strongest asset; they rely to a greater extent on vision.

The

hoof

The critical importance of

the feet and legs is summed up by the traditional adage, "no foot, no

horse." The horse hoof begins with the distal phalanges, the equivalent of

the human fingertip or tip of the toe, surrounded by cartilage and other

specialized, blood-rich soft tissues such as the laminae, with the exterior

hoof wall and horn of the sole made essentially of the same material as a human

fingernail. The end result is that a horse, weighing on average 1,000 pounds, travels

on the same bones as a human on tiptoe. For the protection of the hoof under

certain conditions, some horses have horseshoes placed on their feet by a

professional farrier.

Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Horse&action=history

http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html

Domestic Horse

Conservation status

Domesticated

Scientific classification

|

Kingdom: |

Animalia |

|

Phylum: |

Chordata |

|

Class: |

Mammalia |

|

Order: |

Perissodactyla |

|

Family: |

Equidae |

|

Genus: |

Equus |

|

Species: |

E.

caballus |

Binomial name

Equus

caballus

Linnaeus, 1758